Life on the Sepik, in some ways, seems completely unchanged and unchanging. Most women get up at about five, then paddle their dugout to a good fishing area, where they’ll fish until they have enough fish both to eat and to smoke (later to be sold at market). Later they’ll spend time looking after the kids, tending the garden and any livestock, and cooking the family meals – this last performed squatting over an open fire, typically inside the (highly flammable) wooden and palm thatched house. Men, on the other hand, have a more sporadic approach to hard work – a typical day will see them hanging out in the village spirit house, smoking and perhaps working on some carving to offload to suckers like me and James. Once in a while, however they put on a spurt of activity – only men can build houses (a necessity before one can marry) or dig out a canoe. Men also hunt, mainly for crocodiles which they kill for the skin, mainly with spears or bush knives, exactly as they have done for the past hundred years or more. There’s no running water, no electricity, no TV, no books.

And yet, everywhere one looks, there are the artefacts of modern life. Most people have a cell phone (we never quite figured out how and where they charge them up given there is little or no electricity down river). In a couple of villages, there’s a generator, used in the village guesthouse where the tourists stay but also clearly “borrowed” from time to time by the rest of the village. The village shop sells cigarettes and Coca-Cola (sorry Tek). And the timeless rhythm of the river has of course been most radically altered of all, through the introduction of outboard motors.

There’s definitely a feeling, though, that the Sepik people have taken from the modern world only what they really value. Even in villages with generators, it’s extremely unusual to see electric light in any village houses – what’s the point when there’s plenty of daylight time? The traditional forms of crop harvesting are still used (including the insanely time consuming extraction of sago flour from the sago palm – chop down tree, grate, mix with water, leave starch to settle to bottom, extract, dry) and there’s no machinery used (again, why bother – the plots are so small they don’t really lend themselves to modern farming equipment). Houses are still constructed entirely out of bush materials with no nails, and no locks (there’s no crime – what would you steal?) and are capable of being built by the owner with a little help from a friend or two on the hard parts (putting the upright supports / stilts in place). It’s an entirely organic mixture of old and new and it seems to work pretty well.

The Sepik culture, too, is a curious amalgam of the old traditional kastom ways and the newer ideas espoused by the many missionaries in the area, most clearly articulated in the local church with its mixture of Christian and kastom iconography. Somewhat understandably given that they provide the majority of healthcare and education to the region, the missionaries enjoyed great success at first, with most villagers nowadays proclaiming themselves as Christians. This is undergoing something of a backswing however, with more and more people returning to the traditional ways. Spirit houses, which were abandoned in some villages at the height of the Christianity boom, are being rebuilt and the old kastom ways (use of a clan system to clear up any village disputes; worship of river spirits; initiation ceremonies – including skin cutting) are being revived.

This – oddly – appears partially to have been driven by tourism. One of the fears about going on this sort of a trip to see the “authentic” lives of those less well off than you is that the excursion turns into something like a safari trip – oooh, look at those funny indigenous people doing their funny indigenous things – whilst behind the scenes, the funny indigenous people take off their costumes, relax from their forced poses, and continue with their really very normal day to day life, cursing the tourists for fools as they do so. In the Sepik, there’s more of a feeling that the tourists, with their remunerative interest in the kastom ways, provide an excuse for the villagers to retain some of these traditions and in many ways have revived village pride in customs which they had been taught by the missionaries to despise. No, I don’t for one second believe that the entire area has genuinely reverted to the type of kastom tradition prevalent in the area 50 years ago – and nor would I want to force that kind of stagnation on a region – but rather that the continual presence of (minor – maybe 2-3,000 people a year) cultural tourism has allowed a kind of hybridization to take place which should act to protect some of the older ways and provide an alternative to the blind acceptance of the missionary credo which was (from the sounds of things) becoming commonplace.

The economic impact of modern day life is harder to express. Most people are what we started to refer to as “subsistence affluent” – that is, the quality of life achieved through a subsistence way of life is very high given the area’s fertility and widespread availability both of required food types (protein, starch, vitamins) and building materials. But everyone needs cash for fuel, salt, cooking oil, cigarettes… and we were amazed to find a sort of middle class angst that had set in at least in some villagers – the never ending worry over school fees, despite the fact that this is a country with a 75% unemployment rate and an education guarantees you nothing (our guide, Josh, was a college graduate unable to find work outside the village). School fees can cost around US $2,000 a year if you have a few kids, and I still have no real idea quite how many smoked fish it would take to generate that sum. Provide food and lodging for a tourist for the night, though, and you’re $75 up. We’re one of the best cash crops these people have.

-

-

The villagers farm crocs for their (highly valuable) skin. Feel a bit sorry for the croc!

-

-

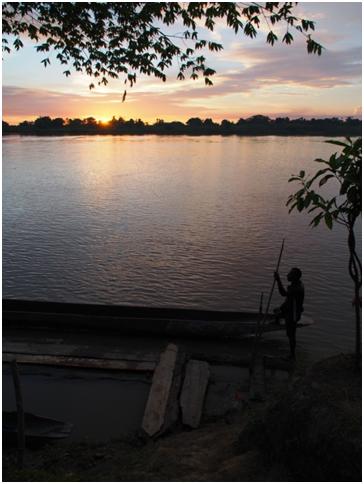

Wow! Check out that motorized vehicle! (Sunset ain’t bad either)

-

-

Mostly, life continues much as it always has…canoes, fishing, canoes….

-

-

Church / traditional imagery perfectly combined in a particularly tribal Virgin Mary

-

-

Traditional culture remains alive…well, at least a long as the dumb tourists (that’s us) pay for it….

-

-

The village where we stayed – except for the Coca-Cola (sorry Tek), unchanged in 100 years